“When I was in India forty years ago,” Swamiji said, “I traveled around the country and lectured in many cities. Even then, it wasn’t easy. At my age now, it would be impossible. How will I be able to reach people?” This was his concern when he left for India in November 2003 to start a work there.

Once he arrived, the solution was obvious. There are several national television stations entirely devoted to religious and spiritual programs. (There was no television when he lived in India forty-five years earlier.) After Swamiji gave a few public lectures in New Delhi, one of those stations offered him a daily half-hour program at a very reasonable rate, about $2000 a month.

To test the water, Swamiji raised enough money from Europe and America to put a show on the air for a few months. He called it The Way of Awakening and based it on his book, Conversations with Yogananda. He opened every show with a chant and ended it with a song. The songs were recorded in advance, but the chants Swamiji did live each time. He did the show in English. Swamiji speaks some Hindi and Bengali, but English was a better choice. It is so widely spoken in India that it is almost the national language.

After he’d filmed a few shows, one of the cameramen said to Swamiji, “This is the most spiritual program we have ever recorded.” Another member of the crew didn’t know much English, but he got the vibration, especially from the music. And during the breaks, Swamiji spoke to him in Hindi. When Swamiji chanted, this man would listen with his eyes closed, often with tears running down his cheeks.

Once the shows began to air, there was an immediate, positive response. People from all over India started calling the ashram. When he went out, strangers began coming up to Swamiji and saying, “I saw you on television.” With his American face and orange robes he wasn’t hard to recognize. Many were deeply moved to meet him and reverently touched his feet.

Once the concept had proved itself, Swamiji decided to use donations from America to put the show on two stations every day, morning and evening at prime times. It would be seen all over India, in many neighboring countries, and, by satellite, even in the United States.

“The most ambitious lecture tour could only reach a few thousand people,” Swamiji said. “Through television, I can speak to millions without leaving home.

“If I have 365 shows,” Swamiji said, “they can run for years without seeming repetitious.” He set aside the month of November to record 235 more—ten shows a day, five days (fifty shows) a week. It was an ambitious schedule, but one of the reasons Swamiji has been able to accomplish so much is that he gives full attention to one project at a time.

* * *

The living room of Swamiji’s house became a television studio. The furniture was moved out; lights and cameras brought in. The set was a simple, comfortable chair placed on an oriental rug. Next to it was a small table with a picture of Master, a bouquet of flowers, and a copy of Conversations. For each show, Swamiji would read an excerpt and comment on it.

Behind Swamiji, as if viewed through a window, was a large picture of the garden at Crystal Hermitage. Around that were a few plants, soft curtains, and a carved Indian screen. Off to one side was a much larger picture of Master that the camera could zoom in on from time to time.

A complicated series of lights and baffles illuminated the set from all angles. Three big cameras were put in place, one directly in front of Swamiji and one on each side. Spectators could sit behind the cameras in chairs and couches against the walls. Having people in the room, listening, helped create a more dynamic atmosphere for Swamiji. Sometimes there were only a handful of spectators, sometimes twenty or more came, comprising a mix of ashram residents, Indian devotees, and visitors from Europe and America.

Swamiji set strict conditions, and repeated them whenever someone new came in. “You are welcome,” he said, “but you must turn off your cell phone.” (Everyone in India, it seems, carries a “mobile.” Phones ring constantly in public places.) “No coughing, no sneezing, and no laughing.” People found this last one the hardest to follow—Swamiji’s humor is irresistible.

He made up a schedule of which excerpt to read and which song would go with it. The songs are all different lengths, so he figured out in advance how long his talk would have to be to accommodate that song. A kitchen timer was set up in front of him, just off camera, so he would know exactly how long he had to speak. Each talk ended promptly on time, and was somewhat less than twenty minutes long.

“How do you know what to say?” someone asked Swamiji. “Usually you tune into the audience, but here you don’t have an audience, just a few spectators and a camera.”

“When I look into the camera,” Swamiji said, “I feel the consciousness of those who will see the program. It’s to them I speak. Master tells me what to say.”

* * *

Conversations with Yogananda is based on notes Swamiji made of his guru’s words during the three-and-a-half years Swamiji lived with him. In 365 programs, he reads and comments on almost the entire book. The result is a complete description of Master—his life, his mission, what it was like to live with him, what it means to be his disciple. Swamiji made these shows to build the work in India, but in the process he created a spiritual legacy for the ages.

“In India, I don’t have to convince people that these teachings are true,” Swamiji said, “or to persuade them of basic concepts like reincarnation, or the need for a guru. It is already part of their culture. I can go deeply into my subject, very quickly.”

When he lectures in the West, Swamiji refers to his guru by name, “Paramhansa Yogananda” to a general audience, “Master,” when speaking to devotees. In India, he says, “my Guru,” like a child talking about his mother.

Before he came to India, Swamiji tended to hold himself in. He rarely revealed the tenderness of his heart and the depth of his own devotion. Now, in India, his eyes often fill with tears and his voice breaks when he speaks of God’s love and the grace of “my Guru.”

“Of all the countries in the world,” Swamiji says, “India feels to me most like home. In America I can share a little of who I am, in Italy I can share more, in India, I can give without reservation.”

Swamiji should have added one more instruction for his spectators: “No sobbing.” Many times the depth of his feeling touched such a responsive chord in my own heart I could barely see him through my tears.

Between each show, Swamiji would pause for five or ten minutes. Sometimes he stood up, though he seldom left the room. It was very hot in the recording studio, especially for Swamiji, who had to sit in front of the lights. The air conditioner was noisy and had to be turned off when the cameras were on. The moment the recording was over, someone would rush to turn the lights off and the air conditioner on. During the breaks there was always a lot of activity around the perimeter of the room, too, because that was the only time people could go in or out.

Sometimes the technicians had to adjust the equipment, or Swamiji would ask for a cup of tea, in which case the pause would be longer. Usually Swamiji chatted with the spectators until the recording was about to start again. Then he became quiet and concentrated as he reviewed the excerpt and confirmed the title of the song.

He spoke to the camera directly in front of him. At one point the director said it would be more interesting it he varied the routine and spoke sometimes to the cameras on either side. Swamiji tried it for one show.

Afterwards he said to the director, “I am sure you are right, but I’m very sorry, I can’t do it. If I have to think ‘Now look to the left, now to the right’ I can’t keep the same level of inspiration. I am speaking to an audience, not to a camera.”

* * *

Electricity in India does not always flow steadily. To compensate for intermittent outages, the house had intermediary panels, batteries, and a generator. Still, the wiring was delicate and the crew had to be careful not to blow out the whole system. Several times an outlet would begin to smoke.

Often the recording had to stop because of something to do with the electricity. Swamiji was trying to keep to a strict schedule of seven shows in the morning and three in the afternoon. But if it was interrupted for reasons beyond his control, he accepted it calmly and without complaint.

Once the whole city lost electricity for an entire day. By the end of the morning session, the batteries were depleted. The generator could recharge them, but not while the cameras were running. They had to stop for several hours.

“Call me when you are ready to start again,” Swamiji said as he went off to his room.

“It isn’t difficult for me to do this,” Swamiji said. “I mean, it is not hard for me to speak. But it does take a lot of energy, and that is what makes it a challenge. And whenever I do something that could help many people, Satan tries to stop me.” Often the attempt to stop him is done through his body's weakness.

Since coming to India in 2003, Swamiji had already done much tapasya, and his physical reserves were low. In just one year Swamiji had bronchitis, pneumonia, dehydration, a broken rib, several incidents of congestive heart failure, and numerous falls.

Many days, Swamiji’s body rebelled against the effort that would be needed to work that day. Yet he had a schedule to follow. Everyone involved tried his best to help him, but the burden was on Swamiji to summon up the strength to carry on. His word is his bond, even to himself. Once he sets his will to something, there is no turning back.

In similar situations in the past, my human heart has quailed and I have urged Swamiji to seek an easier way. Often he has scolded me for my lack of courage. On one notable occasion years earlier, I wanted him to rest, even though he made it quite clear that he intended to go on working. I kept insisting, until finally, with great force, he said to me, “Get Thee behind me, Satan!”

I was horrified! “Am I fighting on the wrong side?” I asked.

“Yes!” he said emphatically, “and I don’t appreciate it.”

He needed me to support his resolution, not to give him reasons for abandoning it. By affirming his weakness, I was in effect trying to undermine his will.

* * *

Somewhere toward the end of the second week of recording, I fixed breakfast for Swamiji, a bowl of cereal and a glass of juice. It was only a few minutes till the make-up artist came, so I left him alone to eat. When I came back to clear the dishes, the food was untouched. He had his elbows on the table and his head in his hands.

“I couldn’t eat,” he said. “I don’t have enough energy to lift the spoon.”

My heart overcame my judgment, and I said to him, “You don’t have to do this.”

Swamiji said nothing, but I knew I had made a mistake. I was not being a true friend. Somehow Swamiji got himself into the studio. As soon as the camera was turned on, it was if the weakness had never been.

“I don’t have the strength to do this,” Swamiji said later, “But Master does. He always gives me the energy I need.”

As the day progressed, the more energy Swamiji put out, the stronger he became. The last shows were among the most dynamic of the whole month. When he exhorted his audience to have the courage to give everything to God, his words rang with the power of his own experience. It was hard to believe that very morning Swamiji hadn't enough energy to lift a spoon.

On many days, Swamiji had to fight the same battle. Satan didn’t give up easily. During the last week of recording, Swamiji telephoned Jyotish and Devi in America. He confided to them, “I don’t know if I can finish.”

Devi said later she was tempted to encourage him to rest, but inner wisdom silenced her. For a moment, neither she nor Jyotish said anything. Then Jyotish responded.

“You have set your will to this,” he said. “You have to do it.”

Again, there was silence. Finally, Swamiji spoke, although he was so moved, he could barely get the words out.

“Thank you, Jyotish,” he said. “Everyone tells me to rest. They mean well, but I can’t rest. I have to do this. You understand. That is just what I needed to hear.”

* * *

Swamiji finished recording the whole year of programs, and they have become, as he knew they would, the cornerstone of Master’s work in India. On December 1, 2004, when it was all done, he sent the following note to many of his friends:

Dear Everybody:

This is an emotional moment for me. I have just finished recording the last of 365 TV programs. I feel I have done a major work for Master, and I am conscious of his happiness in my heart.

There were quite a few days when I didn’t think I could carry on. This last day was especially difficult for me — maybe it was my relief at being near the end. But people couldn’t see what it cost me; it looked easy. Last July (or thereabouts) when I first decided to do the remaining 235 programs in November, I just didn’t dare contemplate the challenge of it: ten programs a day, five days a week, back to back for a whole month and a day.

Last week, to make up for the five extra shows on the last day, I did 13 in one day, and 12 the next. I had many people urging me all month to go slower, but I felt that if I let up I wouldn’t be able to come back and finish the whole job.

As Jyotish said, I’ll reach more people through these programs than the sum of all the people I’ve ever spoken to and written for in my whole life.

I felt like weeping at the end, for sheer gratitude at having finished this job for Master. I didn’t weep, but, as I said, I feel deeply moved. Quite possibly 200 million people, and even more, will view this program, not only all over India, but also in over 100 other countries.

Jai Guru!

Love,

swami

|

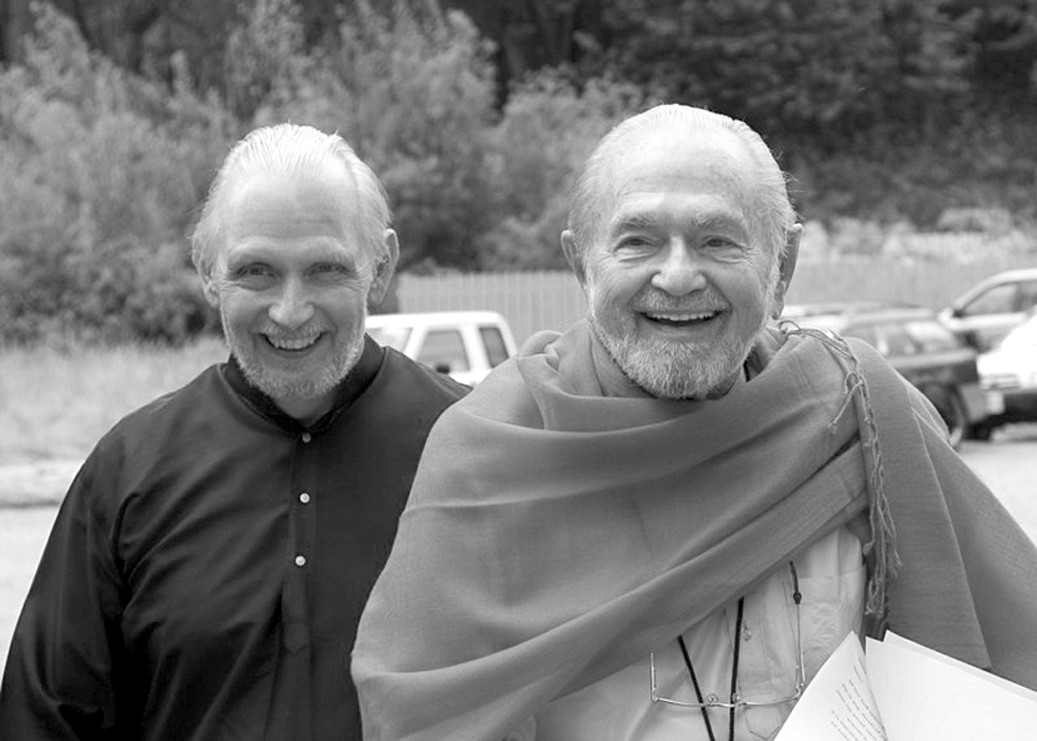

| with Jyotish |

No comments:

Post a Comment