It was Swamiji’s idea to incorporate Ananda Village as a California city. As a municipality, we would have control over our own land use, planning, and zoning. This would get us out from under the county approval process, which had proved to be cumbersome, expensive, and gave our neighbors too much influence over internal community affairs.

Many of our neighbors had come to the area to drop out of society. It was almost a principle with them to oppose all organized groups and strong leaders. Many objected, also on principle, to the population density and some of the land use inherent in having a community. We were not indifferent to their needs, but most of their opposition was not based on anything we had done, or planned to do, but on the fear of what we might do if they did not keep a close watch on us.

In fact, the community is quite self-contained. Most of what happens within the borders of Ananda has no actual impact on those who live nearby. Filing for incorporation was like filing a declaration of independence. Even if we didn’t succeed, we felt it was time to stand up to our neighbors and at least bring the controversy out into the open.

Incorporation proved to be a long and complicated process. After a year and a half of hard work, it culminated in a series of public hearings, then a vote by a seven-member council called LAFCO, the Local Agency Formation Committee. Each hearing drew more people, went on longer, and was more contentious than the one before.

Before the public hearings started, the members of LAFCO seemed to favor our application. We didn’t look like a city, we looked like a farm, but we met the legal requirements for a municipality, and that was all that mattered.

LAFCO was forbidden by law to decide our application on the basis of religion. Even to discuss religion in relation to the incorporation, or to let the subject come into a public hearing, was a violation of our rights. The fact that “Ananda City” would be both a spiritual community and a municipality was like a shadow lurking in the background that could never be brought into the light of day.

The LAFCO members visited the community, met Swamiji, and also met many of the residents. They liked what they saw and for a time it looked like our effort would succeed.

The opposition of our neighbors, however, was our undoing. They were determined, well organized, and came out in droves for the public hearings. We were largely unsuccessful in getting anyone outside of Ananda to speak in favor of incorporation. Gradually the LAFCO members began to side with what appeared to be the majority view: to deny our application.

At the end of the final hearing—which lasted seven hours and was attended by 800 people—only one LAFCO member voted in favor of our application. In that hearing, though, and in several leading up to it, LAFCO allowed extensive testimony from our neighbors about Ananda’s religion and how it would affect the municipality. We protested repeatedly, but to no avail.

* * *

The incorporation effort attracted statewide media attention. After LAFCO voted down the application, I and another Ananda spokesperson vowed in front of the TV cameras to get the decision reversed on appeal, because testimony about religion had been allowed in.

Later, another television crew came to the Village to interview Swamiji. I met them at the community and rode in their car the three miles up the dirt road to Swamiji’s house.

The entire time they plied me with questions about what we planned to do now. I was emphatic that this was just a temporary setback. Our rights had been violated. The process was compromised. This is America. We have not yet begun to fight.

In previous incarnations, no doubt I have been part of more than one revolution, probably including the American Revolution, so this kind of rhetoric comes naturally to me.

When we arrived at Swamiji’s house, he said to the television crew, “I don’t know how much time you were planning to give me, but if you let me have a full five minutes to read a statement I have prepared, I have a special scoop for you.”

I turned to a friend who was there when we arrived and asked him, “What is Swamiji talking about?”

My friend paled, then said, “You don’t know?” He refused to say anything more. The filming was just about to start and I couldn’t ask Swamiji myself.

A few minutes later, in front of the camera, Swamiji started reading the first page of his prepared statement. Immediately I saw that he was speaking of the project in the past tense. That was the scoop. It was over. We weren’t going on.

According to the law, Swamiji explained, LAFCO had acted improperly when they let religion come into the debate. But the fact is religion is the central question. Separation of church and state is one of America’s most cherished principles. Even if “Ananda City” conducted itself in an honorable way—which we have every reason to believe it would, Swamiji hastened to add—to allow Ananda to incorporate would set a bad precedent. LAFCO made the right decision

The moment Swamiji finished speaking the crew turned the camera on me. I had to improvise on the spot all the reasons why I agreed completely with what Swamiji had just said. Of course, I was contradicting everything I had said off-camera just a few minutes earlier, but these crews interview a lot of politicians and it didn’t seem to bother them.

I then took the television crew back to the community, talking all the way about the wisdom of the Founding Fathers and how much we support the basic premises of American life. As soon as they left, I made a beeline back to Swamiji’s house.

“Why didn’t you tell me what you were going to do?” I asked him. I described the scene in the car, how I gave the crew one story on the way over and another story on the way back. “Fortunately, I think fast on my feet.” By this point, we were both laughing. The situation was so ludicrous.

“I’m sorry, Asha,” Swamiji said. “It was a surprise to me, too. When I sat to meditate this morning it just came to me that it was not right for us to go on. It was already too late to reach you.” There were almost no phones at Ananda in those days. Swamiji didn’t have a phone, and neither did I.

“Why didn’t that revelation come to me?” I asked Swamiji. “I’m the one who has been working on the project all this time.”

“Probably because you didn’t ask,” he said.

“No,” I said honestly, “I didn’t. I just went on as if the guidance for today would be the same as the guidance for yesterday. A serious oversight on my part.”

“Yes,” Swamiji said. “It is not wise to presume. You have to be open, and continuously ask Master, ‘What do you want me to do?’”

“I only want to do God’s will,” I said to Swamiji, entirely reconciled now to what had happened. “I threw myself into this project because you asked me to do it and I felt it was right. If you feel it is God’s will that we stop, that’s fine with me.”

Then I added, “I don’t mind losing. I have to admit, however, that our neighbors have been so unkind, in fact at times so downright nasty, that I don’t like the idea that they have won.”

“It is not a matter of likes and dislikes,” Swamiji said. “It doesn’t matter if we lose face, or even if people think we were foolish for having tried in the first place, or for having vowed to go on and then pulling back so suddenly. The only thing that matters is truth.”

“Ahh…. Yes,” I said with a smile, “Where there is dharma there is victory.” Then jokingly I added, “Dharma has served us well so far. No point in changing horses in midstream!”

“Even though we didn’t become a city,” Swamiji said, “I think in the long run our neighbors will respect us more for standing up to them. That’s how they operate and we have to show them we are not pushovers. We can also play their game.”

After that, our neighbors still spoke against most of our proposals, but some of them had been so appalled by things that had been said in the heat of the moment at public hearings that they resolved not to let emotion take over like that again.

Swamiji paused for a moment during our talk, then went on. “Working on this has also been good for you,” he said. “At the beginning, when you spoke in public, you were inclined to tell your listeners what they wanted to hear, rather than tuning in to what needed to be said. Having to stand up to all that opposition at the public hearings has lessened this tendency in you. Now you will be a better minister. That’s the main reason I asked you to do it.”

* * *

Because the incorporation had been such a public event, Swamiji wanted to inform the whole county of Ananda’s decision and the reasoning behind. What he’d written was too long to be printed as a “Letter to the Editor,” so Swamiji bought advertising space in the local paper and printed the following statement:

April 16, 1982

A representative group of us at Ananda met yesterday and decided to go to court over the decision of the Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO) to deny our petition to be granted incorporation status as a municipality. Next week this matter would be taken to the entire community for discussion and final decision. Our legal counsel feels we have a good chance of winning.

The issue, from our own point of view, is clear-cut: We want the freedom to develop, according to law and to the broader interests of Nevada County, but without the restrictions of bureaucratic red tape, and without the all-too-frequent, basically emotional opposition of our neighbors. Our (to us) perfectly reasonable wish has aroused unprecedented, and unprecedentedly emotional, opposition. Ananda has been vilified; my own character publicly slandered. I have repeatedly expressed my desire to work for harmony, and for the general good of all, including the good of our neighbors as much as our own. The press, instead of quoting these statements, has tried to fan the controversy by quoting people who would make me out to be another Hitler, or Jim Jones.

For myself, I am interested in the truth. Lies, whether public or private, are still lies and simply don’t claim my respect. I have consistently affirmed that only two arguments could persuade me not to proceed with our efforts to incorporate: One, that incorporation would not give us the one thing we want from it: greater freedom; and two, that incorporation would actually (as opposed to theoretically) hurt our neighbors. During the LAFCO hearings, no one in the opposition addressed these two issues in such a way as to convince me of the justice of their cause.

Rather, they expressed fears which, our legal counsel assured us, were groundless. They said we might, if incorporated, annex their property. Legal counsel told us they would have plenty of recourse in the event of our wanting to, a thing we would never be interested in doing anyway. They said that as a religious community we would be in conflict with the church-state separation guaranteed by the United States constitution. But the legal decision from Sacramento on this issue was that to deny us on these grounds would be to deny our rights as U.S. citizens. County counsel advised the LAFCO members to reject testimony against our bid on these grounds as invalid. Part of our suit against the county would certainly be based on the evident fact that religion was in fact admitted as a major part of the testimony, and could not but have influenced the final decision against us.

I have always said that truth is my guide—not opinion; not likes or dislikes; but truth. I am not interested in winning, or in saving face. In the present issue, I am only interested in the rights and wrongs of it. I feel that within the limited context of what Ananda’s needs are, and of our contribution, past and future, to Nevada County we were right.

However, last evening, after the meeting at which we decided to appeal, I sat down and read reports on this issue in the national press. As a result I have come to appreciate the problem in the broader context of America as a whole. And I have come to feel that the church-state issue, despite the official pronouncement on the matter from Sacramento, is at the heart of the matter. At stake is not the question of whether I would abuse my power as leader of this religious community. I have never done so. Nor is the issue whether I might do so. I think those who know me are quite certain that I would not. The real issue, however, is whether I could abuse this power. And there we have to say, There are no guarantees that human nature will not express any of its hidden potentials, whether for good or for evil.

Our constitution was written with a clear eye to history, and to the evils that have occurred in the past when any group of people whose interests drew them together for one reason allowed those interests to dictate their decisions in other matters. One of the saddest periods in the history of Christianity was, in my opinion, when Christian teachings became widely enough accepted to become mixed up with national policy.

If, for example, Minneapolis were to become a wholly Christian city, and St. Paul (its sister city) a wholly Jewish one, to the extent that their definition as legal entities became rooted in their respective religious beliefs, I can see the possibility of persecution, perhaps decades down the road.

As long as Ananda was a local issue, our bid for corporate status revolved around land use, self-government, etc. I believe strongly, moreover, and said so at the last LAFCO hearing, that what Ananda stands for in a sociological sense—namely, cooperative effort at a time when our nation is becoming all-too-fragmented—needs to be encouraged, not discouraged.

This very fragmentation, however, that I see taking place on a national level might also be strengthened if religious groups like ours were permitted the status of legal entities. I foresee a time of great stress for this country, when groups will be pitted against one another in an ideological struggle. At such a time, I feel, religion will need to speak out on religious, not political, grounds if it is to be effective for the truth.

In the broader context of America’s history and future directions, I think the LAFCO decision not to grant us corporate status was a wise one. This does not mean I think we were wrong, for what we wanted was valid. This does not mean I think LAFCO’s reasons were necessarily right. But it does mean I think there were higher forces at work here, and that the truths that our neighbors intuited were valid, and a valid reason for concern.

I shall make my recommendation to our Ananda community that we drop the issue.

Sincerely,

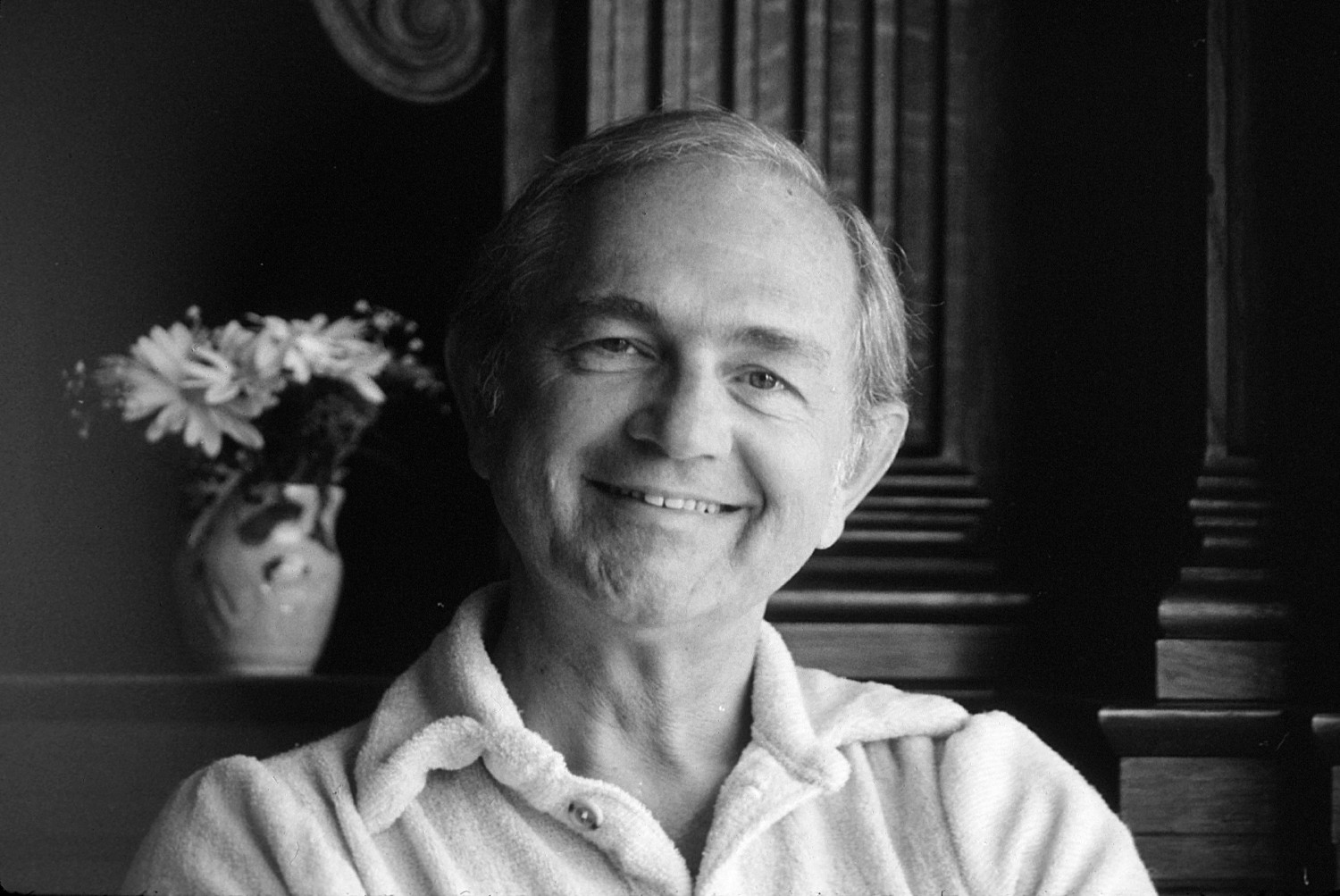

Swami Kriyananda

(J. Donald Walters)

No comments:

Post a Comment